|

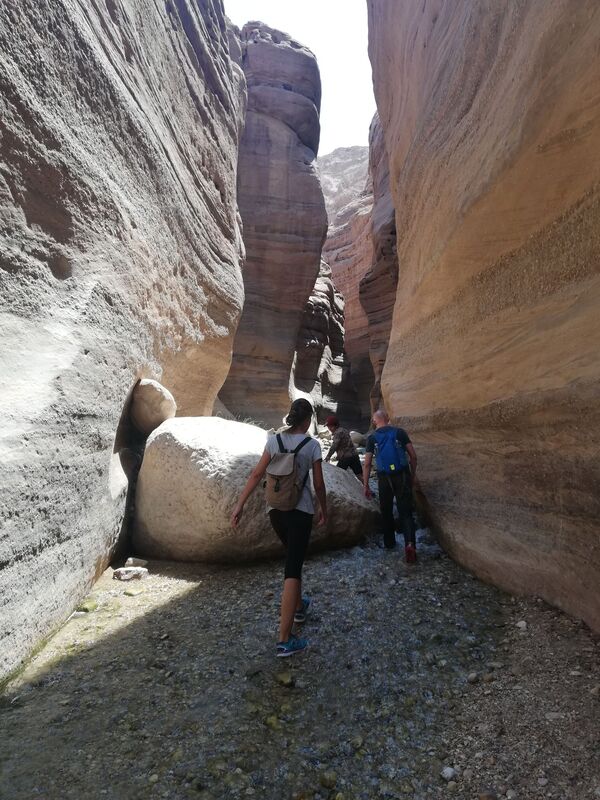

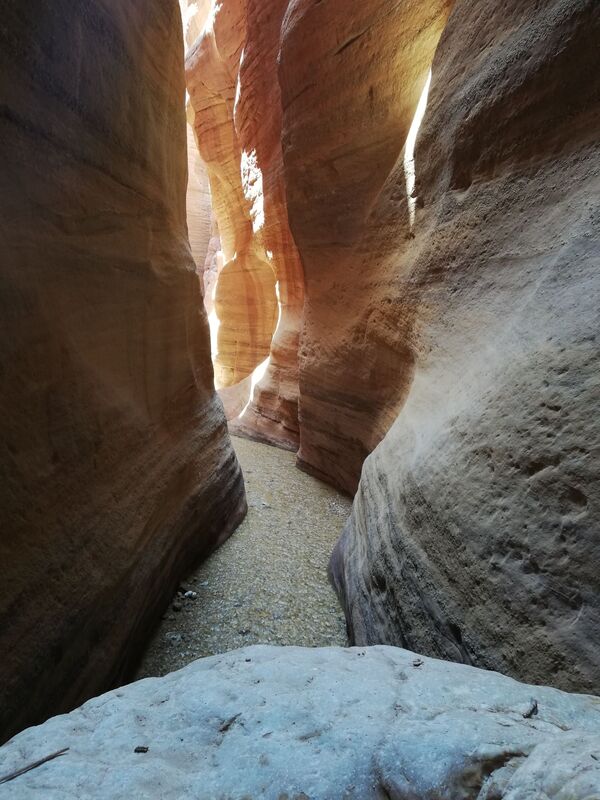

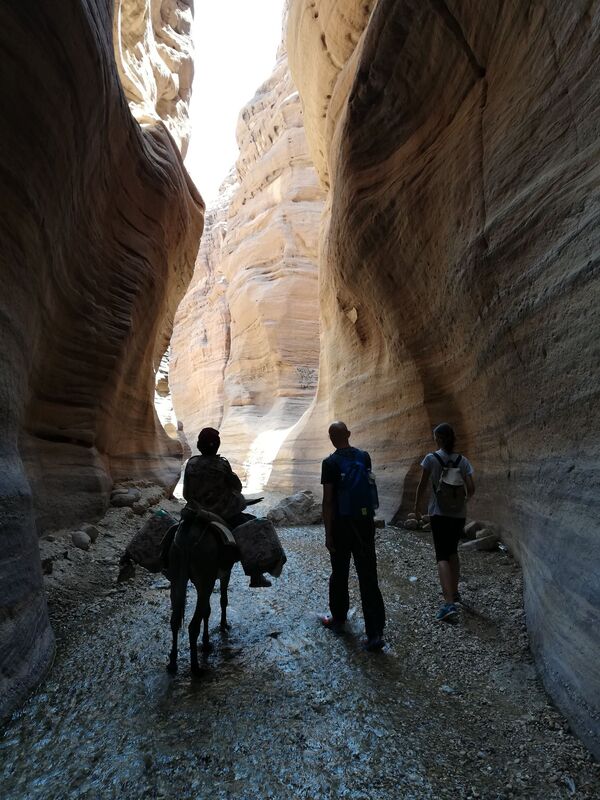

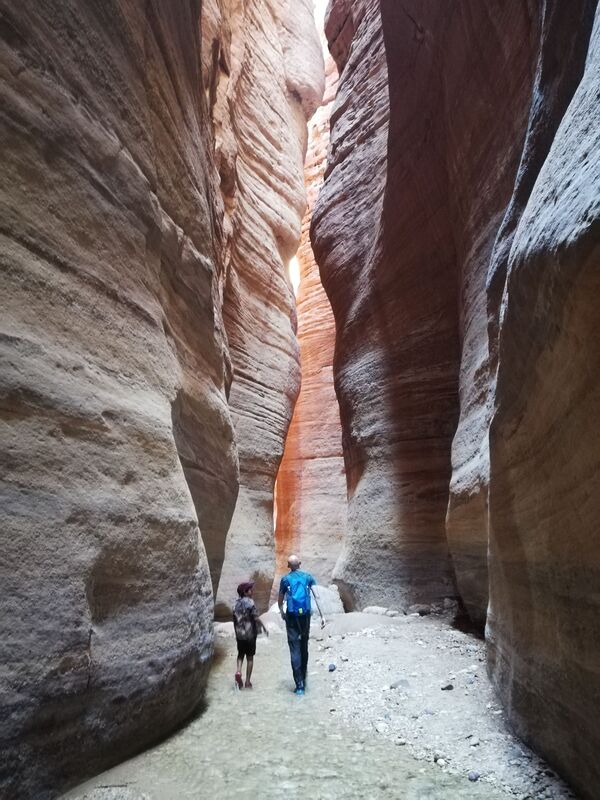

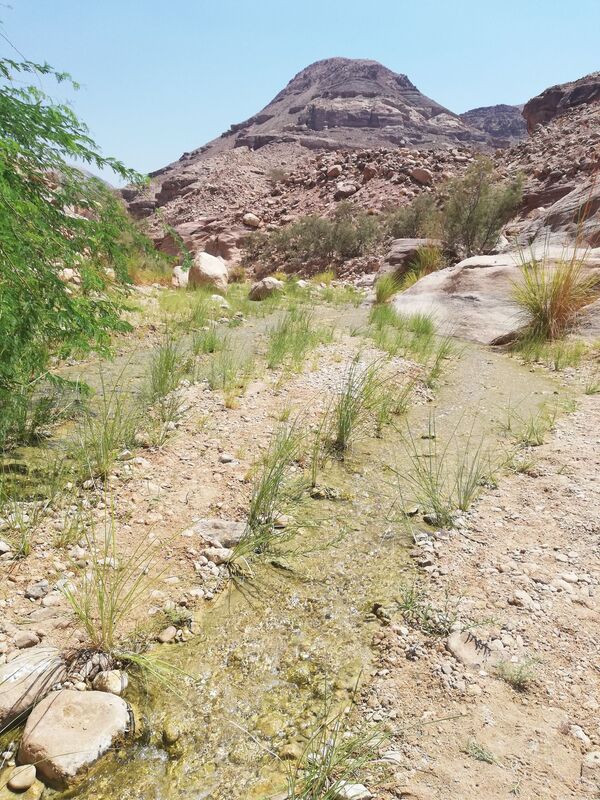

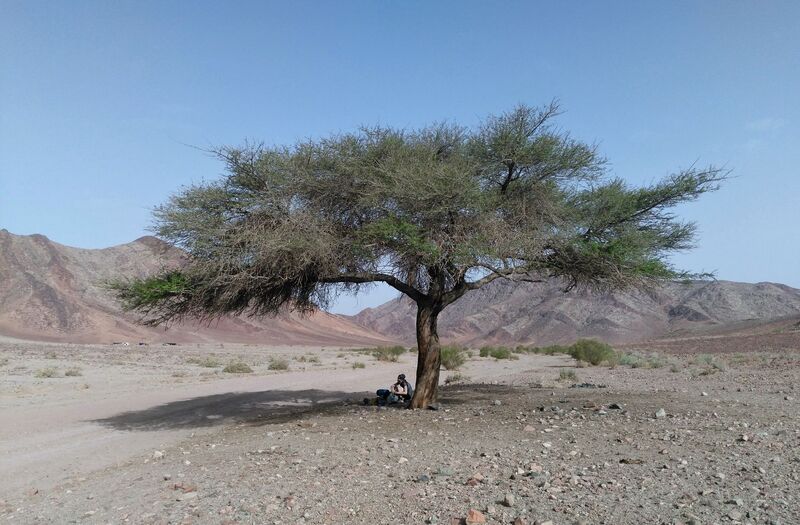

As Jordanian summers can be deadly hot, canyons with water running through them are often the only option to hike without suffering from heatstroke. Wanting to escape the congested capital, Fadi, Eva and I set off for Wadi Karak, a canyon just south of the Dead Sea. Saved by the car whisperer’s magic touch “Car registration, licence and passports,” a police officer commands when pulling us over for a routine check. “Where are you from?” he inquires through the passenger window. “Belgium.” “Welcome to Jordan and good morning.” Looping around the car three times, he carefully considers his next question: “Do you have a fire extinguisher?” A frantic search operation yields no results, yet the officer continues rooting for us: “Search again. I am sure you have one somewhere!” When a second search also turns out to be in vain, he ends up at my window again: “Where are you from?” “Still from Belgium, sir.” “That's in Italy, right?” “Sure.” “Good morning. No problem.” He puts his hands together and nods his head to indicate he will let us off the hook this time. Near the dirt road by the wadi’s entrance, a herd of goats is grazing dust, while the pungent smell of their departed relatives permeates the air. “Wheeeere aaaare youuuu goiiiing?” a voice echoes through the canyon, stopping us in our tracks. “There is no more water there,” a friendly shepherd warns. “The engineers built a dam and took it all. You can drive up to the dam though.” Another dirt road leads us further and further from the village until we reach a Danger: Forbidden Entry sign. “Let’s just see if the dam is around this corner,” Fadi suggests, ignoring my mumbled protests. But karma sure is known to be unkind: a few hundred metres further the car starts to sputter and breaks down. For lack of phone service, all we can do is sit and wait. “39° Celsius,” I read on the display, sweat gushing. “Good thing we have a fire extinguisher ... Oh wait.” Luckily, you can always count on a lifesaver being just around the corner in Jordan and today is no different. A bearded man and his pick-up truck come speeding to our rescue. “Show me what the problem is,” he instructs, while placing his hand on the hood. Instantly, the engine comes back to life. “Are you the Messiah?” I utter, dumbfounded. Visibly pleased with his heroic act, the car whisperer invites us over for lunch, an offer we respectfully decline, as we are still hoping to hike today. Wadi Numeira’s youthful Bedouin guide and his loyal mule It is noon by the time we reach Wadi Numeira, our plan B canyon. As we start our hike, a 13-year-old also rides into the slot canyon on his donkey. “Wanna get on?” he gestures disarmingly. “What’s his name?” “Donkey,” the boy frowns, confused by such an outlandish question. “And yours?” “Zaid.” The stream quickly cools off our feet and shins, as we wade through heaps of trash left behind by locals coming here to picnic: bottles, bags, cups, cans, slippers, diapers, you name it. A few men have driven their cars into the canyon and are unloading their waterpipes and barbecues. Trying to ignore the rubbish by my feet, I look up and let my hand slide over the horizontal lines carved into the rock by the elements over time. The curvy walls look majestic, as the sunrays bring out the entire colour palette: from yellow to orange to deep red. Our youthful guide comes to a halt by a little waterfall and grabs his funnel and bucket, both cut out from plastic bottles. Through a scarf that serves as a filter, Zaid starts pouring water into the barrels on Donkey’s back, a daily chore to provide his family with water. When the job is done, Donkey promptly makes a U-turn and heads home, while Zaid lingers shyly. “He knows the way,” he reassures us and continues with us on our hike. As soon as we climb over the tiny waterfall, the litter disappears, the water is pristine and behind every turn, there is more to marvel at: “Look, a crab,” Zaid points out, spotting the little creature shuffling sideways into a crevice.

A big boulder creates a taller waterfall and blocks our passage, but a few metal handles allow us to climb it. Our little gentleman scouts up ahead, effortlessly hopping from one rock to the next. Along the way, his entire life story pours out: what growing up in a tent as the youngest of 12 is like, how he does not have electricity at home and that he aspires to become an Arabic teacher one day. When the canyon leads to a wider valley, we have nowhere left to hide from the blistering sun and decide to turn back. Zaid does not leave our side until we reach the car safely. I hand him a granola bar, which he politely declines before accepting. Instinctively, he then breaks it in two and offers me the other half. “If becoming an Arabic teacher does not work out, you have a great career as a tour guide awaiting you,” I assure him, eliciting a big smile and twinkly eyes. “Welcome anytime!” he calls out. “If you ever come back, just ask for Zaid. I will be waiting.”

2 Comments

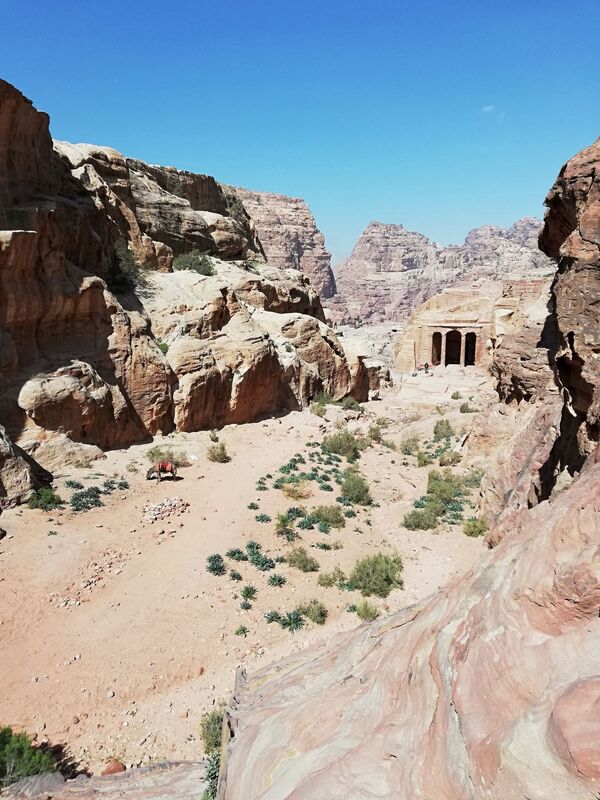

“Don’t worry, mom. Yes, at the hostel. No, it’s not raining,” Fadi reassures his mother over the phone while we devour our falafel sandwiches. The sun is shining and street life in Wadi Musa – the town next to world heritage site Petra – runs its leisurely course. In the morning, we will depart on a four-day trek to complete my last 90 kilometres on the Jordan Trail. But first, we need to drop off water and food in the desert. We arrange to meet with Abu Samra, an acquaintance of an acquaintance, whose jeep will take us to the three sites where we hope to camp. A prolonged quarter of an hour later, he shows up. Contrary to earlier claims, he quickly appears not to know the places we discussed. Miraculously – or, as some might say, alhamdulillah – we manage to reach two sites before the sun goes down. Frustrating, but nothing that can’t be solved by dragging a few extra litres of water with us along the way. A walk through timeWe adjust the straps of our backpacks and zigzag between the many day trippers and carriages through Petra’s narrow siq leading to the Treasury. From there, a side path takes us all the way up to the High Place of Sacrifice, where we admire the 360° views of the surrounding mountains. As we descend into the valley, the hustle and bustle of tour groups and souvenir vendors instantly drowns out. Instead, we now follow the sound of a flute until we find the musician on a stool in front of an ancient temple. Time for tea. Just like his ancestors, Qasem herds goats on the rock flanks. He proudly points to the structure of trenches and wells carved into the massive rocks. The Nabateans – who inhabited Petra during the classical antiquity – were more than aware of the importance of water. An impressive network of waterways supplied all districts with the blue gold from reservoirs higher up. We march on through surprisingly green valleys and climb over crumbling mountains. Having lost track of time, we shift into higher gear, but still arrive at our campsite well past sunset. As soon as we dig up our hidden stash, the barking starts. Seconds later, four guard dogs from a nearby Bedouin camp surround us. A convincing wave with my hiking pole does the trick: the growling transforms into tail-wagging. Our presence is tolerated. Circumventing mountainsWe start the day at 5:30 with knees that don’t want to come along for the ride. Deterred by the prospect of pulling up the tent in the dark again, we carry on. Slow and steady wins the race and despite the GPS duping us into an additional three kilometres, we reach our camping spot as the last rays of light slowly disappear behind the mountain. Victory tastes sweet until we realise our mistake. When hiding our second resupply bag at barely 300 metres from the campsite two days earlier, we had failed to account for the mountain now separating us from our dinner. A thorough terrain study brings relief, however, and the mountain is circumvented. Baked beans and instant noodles never tasted so good. Stubborn desert flowersJordan’s beauty is underestimated. I ignore the pain in my ankles and take it all in: the hills and valleys, the red canyons, the desert sand, the volcano stones and the flowers that stubbornly bloom in their arid surroundings. Just before setting up our final camp, we cross the annual thru-hike organised by the Jordan Trail Association. Nineteen participants from all over the world are taking part. More tea is offered, as well as a whole bag of fruits for the road. After dinner, we are staring at the smouldering campfire and breathtaking starry sky when a jeep approaches. Two men in dishdasha walk over to our tent, blinding us with their torches. I feel my senses sharpen as various scenarios flash through my mind. False alarm. The duo appears to be looking for their friend Abu Sabah, who lives in a nearby village. Tea, tea and a little more teaOur legs seem to have adjusted, so we sprint through the valley. A few kilometres before reaching our destination, we have the pleasure of meeting the legendary Abu Sabah. Receiving us on a mattress around the fire pit in his Bedouin tent, he orders two young boys to prepare the tea. The animated chatter from the women’s section behind the curtain quickly increases in decibels.

Whenever a guest from the village enters, all men stand up out of respect and every passing truck on the dirt road stirs up a lively debate on who is sitting behind the wheel. Everyone knows everyone in the desert. The rusty sign outside Humeima’s visitor centre marks the end of my time on the Jordan Trail. After 652 kilometres, I have crossed the country on foot. We have a celebratory tea with Ibrahim, the ruins’ guard, whose solitary job consists of greeting the handful of visitors. An hour later, Abu Sabah’s son shows up to give us a ride back to our car. "To Petra, correct?" And with a simple Inshallah we fly at 130 kilometres per hour over the narrow roads towards the Rose City. It is close to midnight when we get off the bus at the Desert Highway customs checkpoint. While the bus continues south, Katy and I need to get to Rum village tonight. From there, we will start our hike early morning to arrive on Aqaba's beach three days later. The officers’ amused looks make me suspect that two blonde girls with large packs must not be a daily sighting. “A bus to Rum? You must have missed the last one, but you can wait and see if one passes by.” Two desk chairs are rolled up and soon we find ourselves hanging out with the men in the terminal, indulging in fresh dates from their family farms. When asked why my bag is so heavy, I show them the tent, food and six litres of water. “That’s why my belly is so big,” one of them nods. “I drink a lot of water!” The men burst out in laughter, but before long regain their focus on the gravity of the matter: “But, will you be going without a man? How will you find the way?” “We have our GPS.” Silence. As the only thing passing by seems to be time itself, we give up on waiting for a bus. The officers help us hitch a ride with a lovely family heading to Disi and off we go. Our good friend Khaled“Where are you staying?” the father immediately asks. Our plan of pitching the tent in the outskirts of the village at night likely won’t sit well with him. In my two years in the country, Jordanians have always been very protective of me. To not worry our driver, Katy promptly responds: “We’re staying at my friend Khaled’s house in Rum.” Khaled – a Bedouin whose desert camp Katy had stayed at two years before – is our closest contact in the village. “Great, give me his number so I can let him know you are on the way.” After quickly refreshing Khaled’s memory, Katy hands over her phone and Khaled is notified of our forthcoming arrival. When the road splits, the family leaves us at a police check point a bit before Rum and wishes us well. Not much later, we are ushered into a second car and oblige to our driver’s request to call Khaled again. “Khaled, I have your foreigners, you better pay me or else,” I overhear, but before I get the chance to panic, he laughs: “Oh, don’t worry, Khaled is my friend. I am just messing with him.” When we get to the village, we find Khaled waiting for us in front of his house. I feel embarrassed for the way we have disrupted his evening and am expecting some questions about our sudden arrival. Khaled doesn't hesitate, however, and offers us a place to sleep in his office. No need to walk out of the village and set up our tent in the dark. He even offers us some extra blankets to make sure we will be comfortable. Hospitality at its finest. "Take my gun"After a short night, we set off into the desert. The whole village seems to be looking out for us and several jeep drivers offer us a ride back: “Where are you going? On foot? Without a man? You will get lost. Do you have enough water? Come back to the village with us. No? Then take my gun with you.” With a friendly pass on the opportunity to accidentally shoot myself in the foot later, we plod on through the soft sand, startled only by a snake shooting for the dunes. When we reach Wadi Waraqa late afternoon, we set up camp, collect firewood, rehydrate our rice dinner and enjoy the silence. A Saudi village in JordanWe descend into the valley and locate the well that is indicated on our map. When Katy pulls up the rusty bucket, a yellowish liquid spouts through the holes. Emergency water at best. We follow the narrowing valley until Titin appears on the horizon: a sleepy Saudi town that ended up on the Jordanian side of the border after the two kingdoms swapped land in 1965. We are greeted instantly by bleating goats and chickens scurrying left and right. Not another human being in sight, however, and we must find water before continuing our hike into the arid mountains. Eventually, a young man in dishdasha passes by with a toddler. He guides us to the only shop in town and rushes off to find the shopkeeper. Soon, our new best friend unlocks the metal door and shows us his wares: five shelves displaying biscuits, rice and canned goods, and a fridge filled with soda. We cannot hide our disappointment at the lack of big water bottles, so the shopkeeper offers to refill our empty ones in his house. When we insist on paying him, he refuses steadfastly. Instead, we purchase a feast of Sprite, Pepsi and canned tomato sauce to liven up our cold soaked couscous. For the next hour or two, we escape the hot afternoon sun on the doorstep of his shop, admiring photos of his Saudi bride. “I drive down to see her every chance I get,” he says, holding up his passport chock-full of Jordanian border stamps as proof. The entire male population of Titin passes by to great us. One elderly man has his eyes firmly fixed on my hiking poles and, after a quick demonstration, is delighted to give them a go. When it's time to wake up from our food coma and continue, we quickly realise we have underestimated the scramble required to reach our campsite. The final ten kilometres bear witness to a stream of exhaustion-induced curse words, as I move forward on autopilot. The little energy I have left, is spent on declining the friendly herder’s offer to let us sleep on his farm five times. When we arrive, I am too tired to eat, but ever so grateful to no longer be on my feet. Over the hills to the industrial siteThe spectacular scenery more than compensates for the effort spent clambering over the spiky peaks the next morning. As the Red Sea emerges in the distance, the finish line is in sight.

The real difficulty starts when we leave the mountains behind and enter the industrial site that separates the desert from the beach. For several kilometres, we plough our way through heaps of trash under the scorching sun. Despite our best efforts at stretching whenever we can, every inch of my body aches. When Aqaba’s surf hotels finally appear, my feet sigh in relief. The most refreshing plunge in the sea washes away the sweat, the tears and the extra layer of skin on my big toe. We did it. We crossed the desert, manlessly. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed