|

Visiting Naples? Then most likely Mount Vesuvius is also part of your trip. Taking the shuttle up to the ticket gates, you'll get to peek into the world-famous crater. You might even spot some fumaroles, before buying a souvenir and heading back down with the crowds. Pretty good. But if you’re not afraid to get a little volcanic sand in your shoes, there’s a much better way to do it! We leave our rental Lancia in Ottaviano (at the end of Via Recupe) and hit the trails on an unusually cool day in late May. Mix-and-matching Along the Cognoli (path two) with the Valley of Hell (path one), we finally reach the icing on the cake: il Gran Cono (path five). Most dangerous volcano on earthA shaded forest trail gradually takes us up for the first kilometres. Despite the mild temperatures, the coverage of the foliage is still pleasant. More open, narrow stretches follow, bordered by the yellow and pink of broom and red valerian. While the view of Ottaviano in the valley is beautiful in and of itself, the real magic happens when we turn up a little hill and the giant suddenly looms over us: Mount Vesuvius, causer of great destruction. In 79 AD, an eruption buried the entire town of Pompeii in ash. Although the volcano is in a quiescent stage, it is still an active threat to the densely populated city of Naples. Three million people live near enough to be affected by a future eruption, making the Vesuvius one of the most dangerous volcanoes in the world. But today, there’s not a hint of violence, only awe-inspiring views as we circle the mountain on the gorgeous ridges parallel to it. Hiking up and down mounds of volcanic ash, we regularly have to stop to empty out our shoes. Not only the views of Mount Vesuvius are stunning; to our left, the Gulf of Naples appears below in all its azure splendour. Hell has never looked so lushWe finally descend into the Valley of Hell. Despite its name, it looks nothing like the inferno: lush, lush and lush. The only hellish suffering it inflicts is an acute case of hay fever, when we cross its colourful fields that are in full bloom. Four other hikers, two mountain bikers and countless lizards. Those are all the living souls we meet until the trail joins the paved road that winds up to the ticket gates. Bored bus drivers are parked along the street, leaving their engines running while they wait. Vans manoeuvre in the crowded parking lot and souvenir shops demand our instant attention. Hordes gather by the gates, where the security staff only create more chaos when trying to clear up their confusion. Instant sensory overload. We learn the hard way that we could've saved our lungs the exhaust fumes by taking a little detour to the Gran Cono’s back entrance. This allows you to skip the hustle and bustle in the congested parking lot altogether. Make sure to have a valid ticket, however, as the back entrance is also staffed by a ranger. In our case, a friendly woman opening the gate for us an hour ahead of our reservation. Il Gran ConoUnder the threat of dark, menacing clouds, we swiftly make our way up a narrow trail to reach the popular semicircular ridge. There, we join the crowds to glance into the elliptical crater. At its widest, its diameter is 580 m. Along its inner walls, some fumaroles give us the feeling of looking into an active volcano. No time to linger, though. A thunderstorm is imminent. The first lightning bolts pierce the sky as we start heading back down to the gate. “Guys, descend quickly,” the worried ranger advises us. “Sì, giù giù giù!” Stef acknowledges her concern with the little Italian he picked up the day before, painting a smile on her face before rushing down the sandy slopes. When we return to our B&B that evening, our warm-hearted host Roberto takes a puzzled look at our dust-covered feet. When hearing all about our little adventure, he is certain: “Siete pazzi!” We’re crazy. Though probably not in the sense he intends it, we do agree. We are crazy in love with the mighty mountain towering over his hometown. Practical info

0 Comments

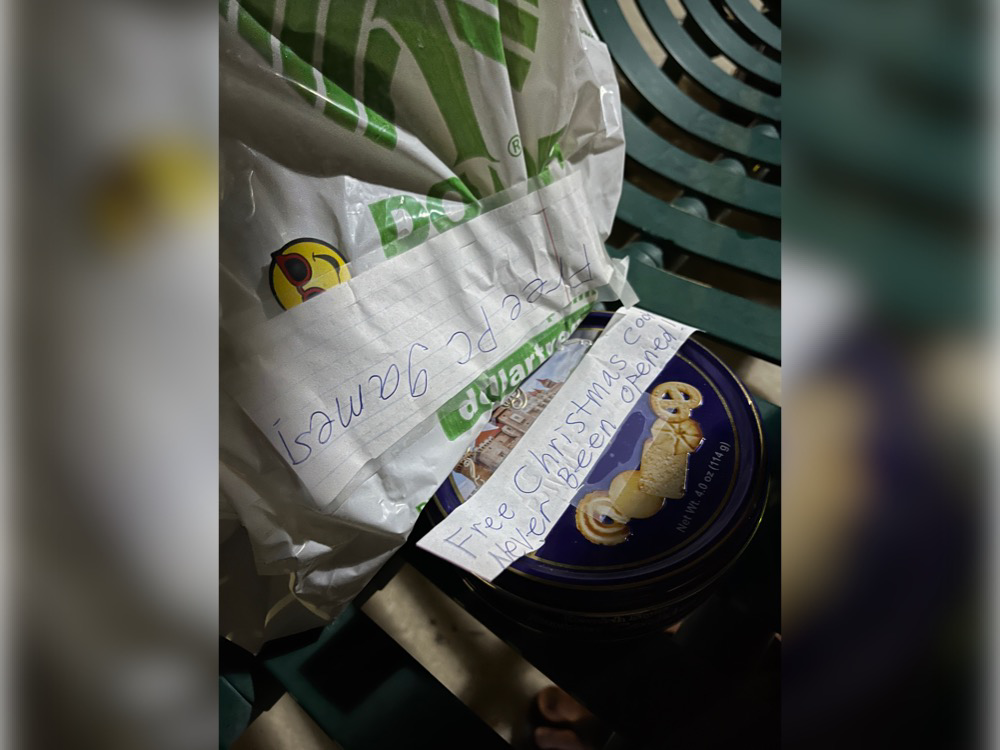

Applause. That’s how every hiker is welcomed to Kennedy Meadows by their peers. We got our round of it this afternoon, when we officially completed the PCT’s Southern California section. 702 miles — or 1.130 kilometres — of desert hiking, which is pretty rad. Or in the catchphrase of our Latino hitch into Tehachapi: “That’s wassup”. For the past two months, we walked through barren hills and green forests. We admired the yucca plants, Joshua trees and colourful flowers, while becoming skilled at avoiding poison oak and poodle dog bush. We hiked through snow and fog, were sandblasted by the wind and melted in the heat. We day hiked, night hiked and siesta-ed during the hottest hours. In short: the desert was diverse, challenging and often surprising. We are fortunate to have made it here without any real injuries, although the hiker hobble most certainly is real. This well-known hiker phenomenon turns my body into that of a 90-year-old for the first two minutes after I get up, no matter how briefly I sat down. The desert also reminded us that growth is often painful and messy. While we were hoping to hike bigger days by now, our average daily pace has plateaued at 27 kilometres. Not getting frustrated when we see other hikers fly by is a lesson we are still learning. Our town days in the desert were almost as colourful as the time we spent on trail. From being offered rides and a bottle of wine to accepting cold drinks, breakfast and coffee from numerous trail angels. We slept in makeshift bunk beds next to a creepy, old doll in Big Bear and stayed with a gun loving Scientologist in Wrightwood. In Tehachapi, we fell victim to the elderly widow’s jokes while hitching a ride and were subjected to her impressive vocal range, as she burst into song before letting us out of her car. My new favourite town hobby is rummaging through hiker boxes on the hunt for free food and gear. I even ate a box of cookies someone had left behind on a bench with a note saying they had never been opened, because free calories. Tomorrow, we head out into the Sierra Nevada with a new pair of shoes, ready to take on different challenges and be rewarded with stunning views. But before we do, here are some random facts about our desert hike:

13%. That’s how much of the PCT we already completed: 342 miles or 550 kilometres. Tomorrow, we will be halfway done with the desert, which is hard to wrap our heads around. As I was loitering outside Big Bear’s post office last week, a German couple asked me how it has been so far. “It has been everything,” was the most honest answer I could come up with. Hot N ColdI figured, why try to find the right words to describe the desert, when Katy Perry has already summed it up so accurately? ’Cause you're hot then you're cold You're yes then you're no You're in then you're out You're up then you're down You're wrong when it's right It's black and it's white We fight, we break up We kiss, we make up (You) You don't really want to stay, no (You) But you don't really want to go You're hot then you're cold You're yes then you're no You're in then you're out You're up then you're down From blistering heat to freezing cold, the desert has most definitely been a lot of yes and no. It was In-N-Out (the burger chain, that is), and up and down (looking at you, San Jacinto). We were wrong when we thought we could send our rain gear home and right when buying those microspikes. It was black from all the burnt trees and white from the snow. We fought tens of blowdowns, briefly broke up with the trail when hitching a ride into Julian for a doctor’s visit, but kissed and made up when we were awe-struck by the Whitewater Preserve. We didn’t really want to stay another day in Idyllwild to wait out the storm, but we also didn’t really want to go. It definitely was hot and cold, yes and no, in and out, up and down. Mental hoopsWe are doing great physically. Apart from feeling tired most days and a few blisters here and there, our bodies seem to be handling the daily exercise well and have already gotten stronger. Instead, it is the mental hoops the trail is making us jump through that have been the bigger challenge so far. Constantly being on the move felt draining at first and by trying to keep up with other hikers, we became very focused on our pace. We pushed harder than we should have until we felt burnt out and were questioning why we were even out here. I was frustrated that my legs could “only” carry me 15 miles a day and felt pressed to get up early every morning to rush to the next milestone. There’s also quite a bit of keeping up appearances on trail. Many hikers claim to be “just cruising,” “feeling absolutely fantastic” and “loving every minute,” as they “crunch those miles.” Listening to these narratives made us feel inadequate at times for not always having a blast. Don’t get me wrong, there are definitely amazing moments, but it is also a lot of hard work and discomfort. For the first two weeks, we were just going through the motions of thru-hiking: packing up, making miles, completing camp chores and sleeping. We were checking the same boxes over and over again without having the energy to enjoy the beauty that surrounded us. Eventually, we realised we were carrying a lot of social pressure with us on trail, while one of the main reasons for us to be here was to get away from exactly that. So one morning, when everyone had already left by 6:30 to sprint up the mountain, we decided to slow down instead. We watched the hummingbirds drink, the gopher dig and the rattle snakes sunbathe. And it was glorious. HYOH (hike your own hike) might be a popular hashtag, but the concept probably isn’t practised enough yet on trail. So from now on, this hike is about me. It’s about us. As much as I would love to reach Canada at the end of all of this, arriving anywhere is no longer the main goal. We’ll get to wherever we need to be, while taking it all in and enjoying our time with the people around us. Trail magic and communityEven though we don’t have our trail family yet, we do have the pleasure of hanging out with some pretty cool people whenever we run into them.

Take Michael, who passionately told us all about the moose he photographs back in Colorado, or Jonah, Kate and Xander, who taught us the important skill of eating Oreos handsfree. And then there’s Graham, who convincingly argued that the birds are just singing about cheese burgers all the time, or Becca and Andrew, who stepped into horseshit right in front of our eyes one day and who we ended up boating with on Big Bear Lake the next. What also helps us keep going, are the many encouragements and acts of kindness from strangers. It’s trail angels such as Francesca, who helped me plan a surprise birthday party and went out of her way to help us get the necessary medication when the nearest pharmacy was an hour away from us. It’s the lady who brought us donuts in the parking lot and people we never even met, who left us grapefruits under the underpass or a cold soda after a harrowing 30 kilometre descent. It’s people like Mario, who spontaneously offered us a ride back to the trail, while we were just having ice cream outside a gas station. It is all the passersby that strike up a conversation and encourage us. While Canada is still too far to even think about and thru-hiking will always be a lot of hot and cold, we are finding more and more joy in this strange hikertrash lifestyle every day. To test our gear one last time before hitting the Pacific Crest Trail, we explored the Sûre valley and its beautiful rocky ridges on the Lee Trail, one of Luxembourg’s finest hiking trails. In three sunny days and two freezing nights, Katrien, Stefaan and I hiked the trail's 52 kilometres from Kautenbach to Ettelbruck. After setting off from Kautenbach, we immediately got served the first of many steep climbs. With 2,000 metres of elevation gain, the trail is nothing if not demanding, but the scenery is worth the exertion. In 2015, the route was awarded the European label 'Leading Quality Trail' for good reason: largely unpaved, great viewpoints, clear waymarks and easy access to public transportation along the trail! Photos by Katrien Rigo, Stefaan Van wal and myself

Practical information:

“You’re not going alone, are you?” In every conversation I have had about my upcoming PCT thru-hike, the question has popped up. Initial enthusiasm quickly fades into concern, until people learn that I am starting off with my boyfriend. “Oh, that’s fine then, because all alone …” For the longest time, I assumed everyone setting off on an epic adventure, such as hiking all the way from Mexico to Canada, received the same level of concern. Turns out that’s not the case. I recently asked my partner whether he gets the same reactions: “People do ask me if I am going alone, but their main worry is that I will be lonely, not that it would be unsafe.” The funny thing is that not everyone seems to mean “it’s good that you’re going with someone,” when they voice their relief. What they are really saying – perhaps even subconsciously – is that it is good that I am going with a guy. When I set off on hiking trips with female friends in the past, not all sceptics were reassured. Conclusion: while going with another woman is good, being accompanied by a man is still considered safer. Gender-based concernThe disapproval of me adventuring solo is often phrased very subtly. Sometimes as direct criticism, but usually it takes the form of well-intentioned concern. And concern is not a bad thing. It is a sign of love and care that should be taken into consideration. But it becomes problematic when it is tied solely to my gender instead of to my skills and experience level. While there are still very real risks involved with being a woman in most places in the world, the dangers I am most likely to face in the wilderness will not discriminate. A bear does not care about my gender. A river will not pull me under more. A tree is not more likely to fall on me. And I am not more prone to slipping and falling, getting lost and dehydrated, or being struck by lightning than any man on trail. And yet, the narrative I hear time and time again implies that I am somehow more fragile and less capable of making it on my own in the backcountry. While male peers are encouraged and praised for their bravery and strength, I am regularly told – directly and indirectly – that I am simply “lucky” nothing has gone wrong so far. The message is clear: it is not my careful evaluation of situations and sound judgement that guide me through adventures safely, but sheer luck. It is only a matter of time before my “irresponsible behaviour” turns me into the next headline, if I am to believe the critics. "Concern becomes problematic when it is tied to your gender and not to your individual skills and experience level." Rethinking the narrativeThe human brain is wired to believe the information it is fed systematically. Narratives like these leave women – like myself – feeling insecure and hesitant to take on challenges. They place mental barriers in the way of women wanting to explore the outdoors and instill misplaced fears they will actively need to overcome to pursue their goals.

On this International Women’s Day, let’s rethink the narrative. It is ironic that we still teach women to ignore and downplay inappropriate male behaviours that could actually harm them, yet discourage them from going after empowering experiences that will better equip them to stand up for themselves in the face of real threats. So when I set off soon, show me that you care, but do not ask questions you would not ask if I were a man. Because quite frankly, I am tired. Tired of being deemed lucky instead of capable. Tired of hearing the world is too dangerous for me and that it would be foolish to think otherwise. Tired of having to prove my worth, while I know the strength that resides within. Care to break a leg next time you’re out hiking with me? Develop mild hypothermia or suffer from heat stroke? You’d be in good hands. After four days of lectures, drills and simulations, I am officially Wilderness Advanced First Aid certified! In December, Stefaan and I signed up for a four-day Wilderness Advanced First Aid (WAFA) course taught by Wilderness Medical Associates International and hosted by Outward Bound Belgium at the Chateau Varoy in Anhée. From 8:30am until 6pm, we broke limbs, burnt ourselves, fell out of trees, got hit by lightning, cut our arms, went unresponsive, developed severe hypothermia, had allergic reactions, experienced volume shock, hit our heads, choked, suffered from urinary tract infections, had strokes and heart attacks, … You name it, we had it! Four intensive days of lectures and drills taught us how to assess emergency situations and provide medical assistance in the field. We also learnt to determine when an emergency evacuation is necessary and how to get a patient out as safely as possible, while also keeping ourselves and others out of harm’s way. Signing up for a WAFA course had been on my mind for years, but it turns out that I am incredibly skilled at making up excuses. Medical conditions have made me squeamish for as long as I can remember, sometimes even making me faint. But with huge hiking plans on the horizon, it only felt right to do the responsible thing and finally take the course … … which leads me to the big announcement. Two years after the pandemic cancelled my plans to thru-hike the Pacific Crest Trail, Stefaan and I will finally be setting off from Campo this April! If all goes well, we should arrive at the Canadian border sometime in September. I sincerely hope none of my future blogs will include any of the techniques we practised during the course. But if disaster does strike, I now feel confident that I will handle the situation in the best way possible. While first aid courses aren’t cheap, that peace of mind is priceless to me. Photos by Diederd Esseldeurs, Stefaan Van wal and myself

The sensation of dry feet feels like a distant memory after four rainy days on the GR 738. But on day five, I can pat myself on the back for making it through the solo part of my adventure. At the popular lodge La Martinette, a Belgian companion is waiting for me. In addition to good morale, Stefaan is bringing four days worth of food – a welcome resupply on a trail that does not pass through many towns. Sleepover parties with Pierre, Pierre and the 1970s Larousse After a warm night at La Martinette, we put on our rain gear to defy the showers coming at us from all sides on our 1.200 metre ascent towards the Refuge des Sept Laux. Above the treeline, the trail has transformed into an icy stream reaching up to our ankles. Soaked to the bone and shivering, we knock on the door of the fully booked refuge three hours later, but the grumpy staff show no remorse. Commanding us to wait outside, they collect our money and hand over the key to a dilapidated shed ten minutes away. “At least we’ll have a roof over our heads,” I cautiously try to salvage the situation. With red, swollen hands, I frantically peel off my wet clothes when we stumble inside. Stefaan picks a battle with the fire stove, while I crawl into my sleeping bag and wait for my extremities to regain some sensation. My feet finally start to tingle when we are joined by butcher Pierre and teacher Pierre, our new housemates. Pages ripped from a 1970s Larousse help keep the fire alive all evening. With the remainder of the encyclopedia, Pierre and Pierre subject us to a challenging game of guessing which word they read the description aloud to. Malheureusement, our grasp of the French language is not quite up to par. What could have been a miserable night in our tents, turns into a candle-lit sleepover party instead, with a three-course meal followed by a couple of beers – I did learn how to hike like the French just two days ago. The cherry on top of the cake is the starry 4 AM sky that heralds a better weather window for the coming days. Un pierrier de merde A humble rainbow brightens up the chilly morning, as we hike past several lakes. Though we only have one outfit on us, we manage to change multiple times an hour by putting on and taking off layers. I wonder what the birds must think of our constant metamorphosis, knowing all too well the answer is probably nothing at all. Nature couldn’t care less, which is one of the things I love about it. To avoid the remaining snow patches, we take a little detour and hop from one rock to the next all the way up to the Col de la Vache, where a griffon vulture circles overhead in search of carrion. A middle-aged hiker approaches from the opposite valley: “Good luck with your descent,” he snorts, “a pierrier de merde awaits you on the other side.” A serious scramble does require our utmost attention going down, but spotting a sunbathing chamois and a furry marmot family makes the effort worthwhile. Under the setting sun, we set up camp on a patch of grass by a little stream and enjoy our bivouac’s stillness with Grenoble’s gentle glow in the valley behind. For the love of crackers We take our time getting ready in the morning, while the sun dries our tents. Descending past the Refuge Jean-Collet, we admire the extensive views over the Chartreuse before toiling up a steep hill to the Col de la Sitre. With two gorgeous valleys stretching out on either side of the rim, I feel on top of the world both physically and mentally. By the Lac du Crozet, we run into our new pal Robert and his friends once again. “Are you excited to have tarte aux myrtilles at the Refuge de la Pra soon?” Thibaut beams. Unaware that blueberry pie was even an option, we are indeed thrilled by the prospect. Eventually, it is the fresh crepes on the sugar-ridden menu that manage to seduce us. We team up for a group bivouac by the Lacs Robert, trading our parmesan and olive oil for sips of beer. As the crackers and Nutella jar make their way around the circle, eyes close in pure delight at so much goodness. A spirited round of “Zhe Game” and some star gazing top off the night. All that separates us from society is a short descent to ski resort Chamrousse, where pop music blasts through giant speakers. Tourists stroll past market stalls selling regional produce, while their shrieking offspring go nuts on a Spongebob-shaped bouncy castle. A minute ago, we were tracing our way through a herd of goats. Now, days’ worth of unanswered texts light up our phones and I cannot help but stare at waitress' fake eyelashes as she takes our order. “Life in the mountains has its own pace,” I sigh. But my melancholy is short-lived, evaporating the minute our crepes and cappuccinos are served. Before we hop on the bus to Grenoble, I make sure to pick up a bottle of génépi from the market – a little something to ease the mountain nostalgia back home, just in case ... Practical info

“Why on EARTH would you want to hike in the mountains all by yourself?” Though far from the words of encouragement I am hoping for, my mom does make a fair point. Why DO I want to hike at least a good part of the GR 738: Haute Traversée de Belledonne solo? I mumble something about the need to leave my comfort zone after cocooning during the pandemic, but I suspect it is my fear of hiking and camping alone I really want to confront. As I swing my pack over my shoulder and say my goodbyes, I attempt to look confident, though in reality, I am terrified. What if certain stretches of the trail are too technical? What if there is still too much snow? What if a storm erupts when I am on a ridge? What if the guy I asked for advice in that Facebook group was right and I can’t handle the brutal changes in elevation? Secretly, I pray for an excuse to pop up, anything that will allow me to bail. But no such excuse presents itself, so off to the French Alps I go. Un orage exceptionnel The thunder makes my AirBnB in Aiguebelle shake at night, which does not ease my anxiety. A little note on the breakfast table in the morning does, however: “Chère Lien, if it may reassure you, last night's storm was truly exceptional. We are sure everything will be just fine.” As I make my way out of town, clouds dance around the peaks surrounding me. The abandoned Fort de Montgilbert – built around 1880 to keep an eye on the valley – looks eerie in the mist, encouraging me not to linger. Forest trails take me up and down hills all day until I reach the Baraque a Michel, an unguarded shelter in the woods, featuring nothing more than a wooden table and a tiny window that barely lets in any light. The predicted storm could hit soon. As I weigh my options, the sound of someone slamming on the brakes makes me look up. A man and his mountain bike are staring right back at me: “Will you sleep here tonight?” There it is, the number one question feared by most female hikers, closely followed by “Are you out here all alone?”, which just so happens to be his next inquiry. Debating whether I should make up an imaginary friend, I stutter: “Uhm, I am not sure yet. I will decide later.” Trying to keep a calm demeanour, I nudge him to leave: “Have a good rest of your day!” Luckily, he takes the hint. To my throbbing calves’ dismay, I gather my things and rush to the next cabin: the Baraque de la Jasse. Just as I have rolled out my sleeping pad and gotten acquainted with the resident mice, the thunderstorm erupts. Hail the size of marbles and violent gusts of wind batter against the thin walls all night. “Anything to not be in my tent right now,” I whisper to myself, as I drift off to sleep. Eau de chien mouillé It is still pouring in the morning. Rhododendron-lined trails lead me to the next shelter, where I kick off my shoes and wait for my body to stop shivering. Setting off alone, one of my biggest doubts was how I would handle challenging circumstances. When hiking with a partner, you do not have the luxury to throw off your pack and wallow in self-pity for hours. You keep it together. When hiking solo, well, you could. I am proud to notice that quitting does not feel like an option, however, even as I wiggle my soggy feet back into wet socks. The trail is narrow and rocky. The rugged contours in the fog and the sound of the river gushing in the valley make me suspect that the landscape must be stunning on a clear day. When the Refuge des Ferices finally appears around the bend, smoke is already blowing from the chimney. With another storm lingering, I call it home for the night and greet my roommates: six middle-aged hikers and one soaking wet husky. Over homemade bread, I listen to their stories about how the French are never quite satisfied, while the fire crackles nicely. Damp clothes hanging from every beam and nail in the room are checked impatiently for the first signs of dryness, but to no avail. One by one, my companions decide to throw in the towel and come back another day when the weather gods have been appeased. Tormented by their animated fantasies about warm showers, soft sofas and comfy sweaters, I retreat to my bunk. On doit manger bien

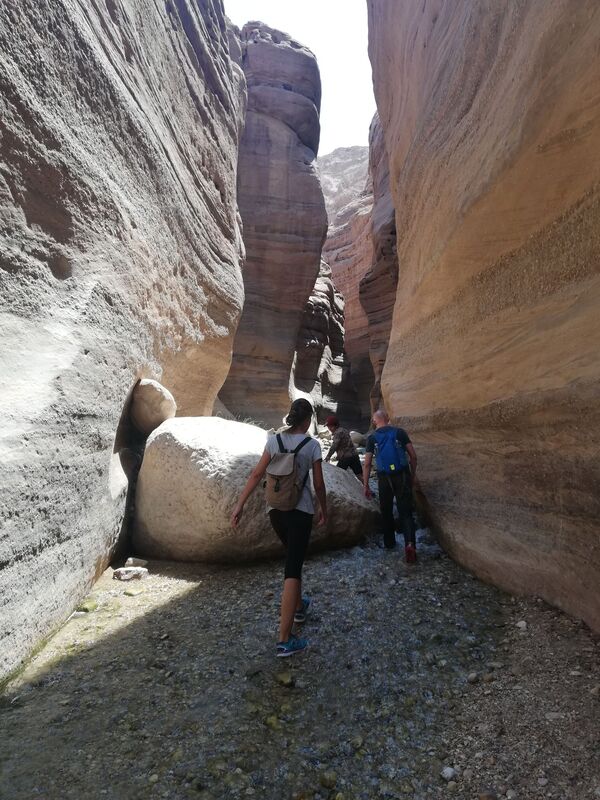

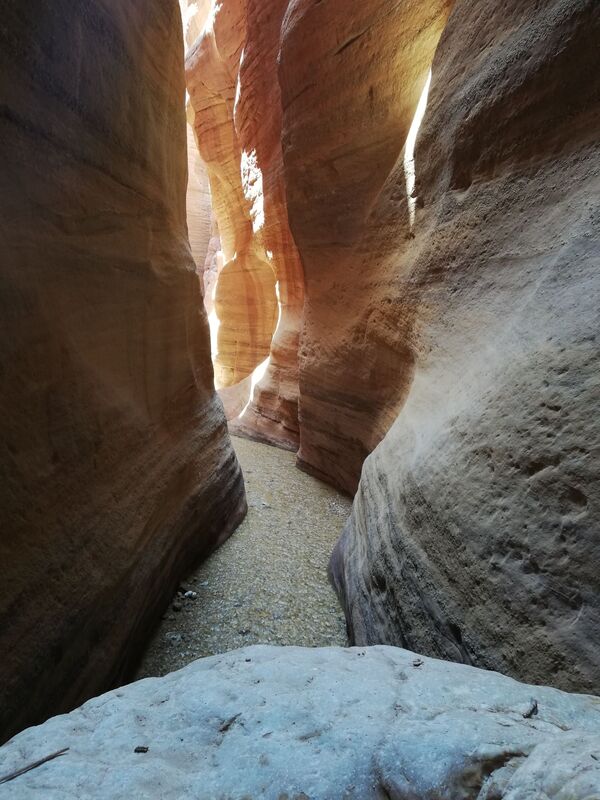

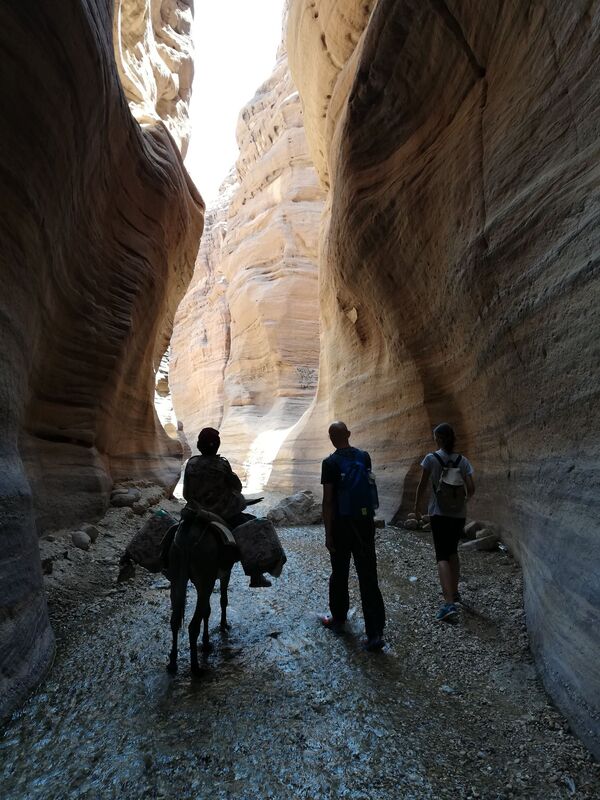

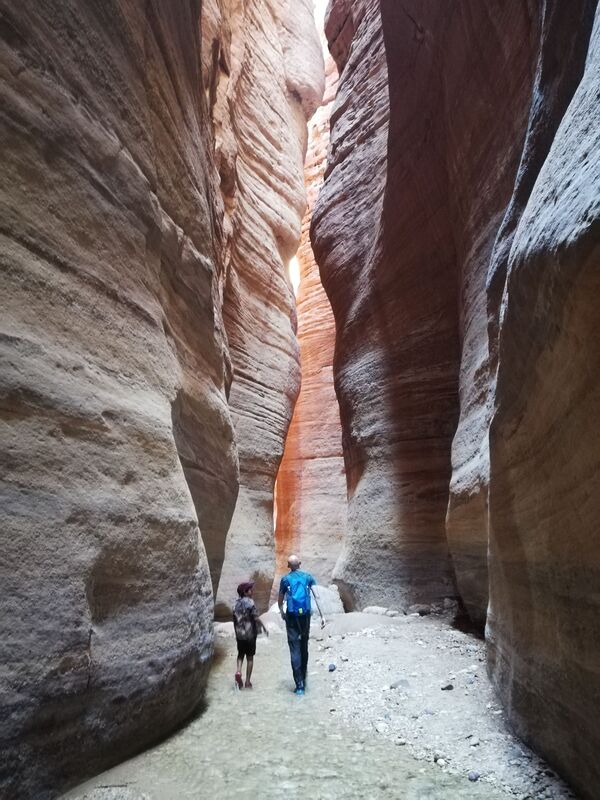

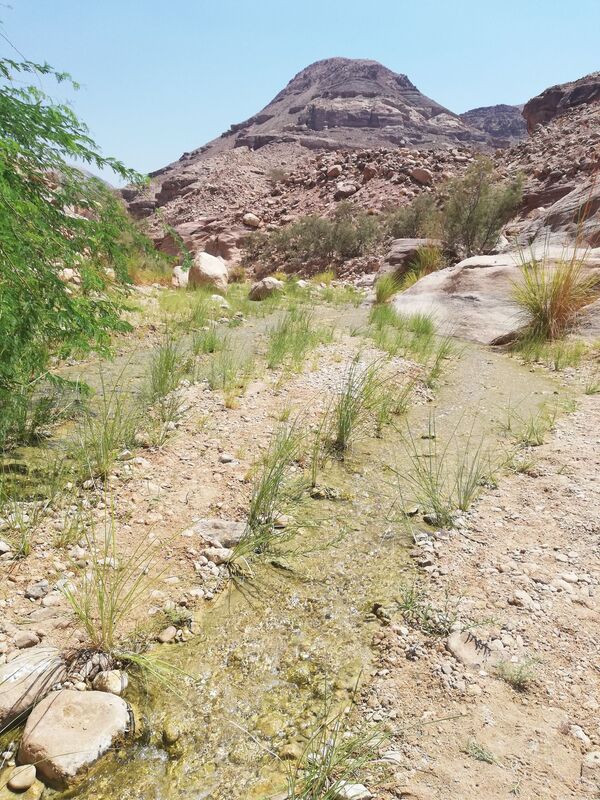

As the first sunrays clothe the mountain peaks in orange hues, I shiver in the shade in front of the refuge. “Judging by the white hair on my shoes, I believe your little friend may have used them as her mattress last night,” I confide in the husky’s owner, who chuckles and offers me a cup of fresh mint tea. “At least that gives me a valid excuse for their odour,” I argue. The fog feels like an old friend accompanying me on my ascent to the umpteenth col hidden from sight, as I set off solo again. But then my luck drastically changes: the clouds lift and a glorious valley appears at my feet. With a stupid grin on my face, I descend so cheerfully I could skip. Late afternoon, I pitch my tent outside L’Aup Bernard, where a group of friends is sneakily putting up bows and other decorations. “It’s Robert’s 30th birthday tonight,” one of them winks. “You sure didn’t spare any effort,” I applaud them, as a never-ending string of supplies emerges from their packs: a tablecloth, candles and enough food for a three-course meal. Robert jovially invites me to join the party, so I gladly nibble on crackers dipped in fresh hummus, sample the pasta with truffle pesto, devour a brownie while singing birthday songs and sip some génépi – a local herbal liquor – as a night cap. “The French don't mess around with their meals,” I note. “Ah yes, évidemment, one needs to eat well,” Robert shrugs. Way past hiker midnight, I crawl into my sleeping bag with a full belly and a big smile on my face. The trail may challenge, but it surely also provides. Turns out 65 kilometres is just enough to make my pre-departure fears feel like a million miles away. As Jordanian summers can be deadly hot, canyons with water running through them are often the only option to hike without suffering from heatstroke. Wanting to escape the congested capital, Fadi, Eva and I set off for Wadi Karak, a canyon just south of the Dead Sea. Saved by the car whisperer’s magic touch “Car registration, licence and passports,” a police officer commands when pulling us over for a routine check. “Where are you from?” he inquires through the passenger window. “Belgium.” “Welcome to Jordan and good morning.” Looping around the car three times, he carefully considers his next question: “Do you have a fire extinguisher?” A frantic search operation yields no results, yet the officer continues rooting for us: “Search again. I am sure you have one somewhere!” When a second search also turns out to be in vain, he ends up at my window again: “Where are you from?” “Still from Belgium, sir.” “That's in Italy, right?” “Sure.” “Good morning. No problem.” He puts his hands together and nods his head to indicate he will let us off the hook this time. Near the dirt road by the wadi’s entrance, a herd of goats is grazing dust, while the pungent smell of their departed relatives permeates the air. “Wheeeere aaaare youuuu goiiiing?” a voice echoes through the canyon, stopping us in our tracks. “There is no more water there,” a friendly shepherd warns. “The engineers built a dam and took it all. You can drive up to the dam though.” Another dirt road leads us further and further from the village until we reach a Danger: Forbidden Entry sign. “Let’s just see if the dam is around this corner,” Fadi suggests, ignoring my mumbled protests. But karma sure is known to be unkind: a few hundred metres further the car starts to sputter and breaks down. For lack of phone service, all we can do is sit and wait. “39° Celsius,” I read on the display, sweat gushing. “Good thing we have a fire extinguisher ... Oh wait.” Luckily, you can always count on a lifesaver being just around the corner in Jordan and today is no different. A bearded man and his pick-up truck come speeding to our rescue. “Show me what the problem is,” he instructs, while placing his hand on the hood. Instantly, the engine comes back to life. “Are you the Messiah?” I utter, dumbfounded. Visibly pleased with his heroic act, the car whisperer invites us over for lunch, an offer we respectfully decline, as we are still hoping to hike today. Wadi Numeira’s youthful Bedouin guide and his loyal mule It is noon by the time we reach Wadi Numeira, our plan B canyon. As we start our hike, a 13-year-old also rides into the slot canyon on his donkey. “Wanna get on?” he gestures disarmingly. “What’s his name?” “Donkey,” the boy frowns, confused by such an outlandish question. “And yours?” “Zaid.” The stream quickly cools off our feet and shins, as we wade through heaps of trash left behind by locals coming here to picnic: bottles, bags, cups, cans, slippers, diapers, you name it. A few men have driven their cars into the canyon and are unloading their waterpipes and barbecues. Trying to ignore the rubbish by my feet, I look up and let my hand slide over the horizontal lines carved into the rock by the elements over time. The curvy walls look majestic, as the sunrays bring out the entire colour palette: from yellow to orange to deep red. Our youthful guide comes to a halt by a little waterfall and grabs his funnel and bucket, both cut out from plastic bottles. Through a scarf that serves as a filter, Zaid starts pouring water into the barrels on Donkey’s back, a daily chore to provide his family with water. When the job is done, Donkey promptly makes a U-turn and heads home, while Zaid lingers shyly. “He knows the way,” he reassures us and continues with us on our hike. As soon as we climb over the tiny waterfall, the litter disappears, the water is pristine and behind every turn, there is more to marvel at: “Look, a crab,” Zaid points out, spotting the little creature shuffling sideways into a crevice.

A big boulder creates a taller waterfall and blocks our passage, but a few metal handles allow us to climb it. Our little gentleman scouts up ahead, effortlessly hopping from one rock to the next. Along the way, his entire life story pours out: what growing up in a tent as the youngest of 12 is like, how he does not have electricity at home and that he aspires to become an Arabic teacher one day. When the canyon leads to a wider valley, we have nowhere left to hide from the blistering sun and decide to turn back. Zaid does not leave our side until we reach the car safely. I hand him a granola bar, which he politely declines before accepting. Instinctively, he then breaks it in two and offers me the other half. “If becoming an Arabic teacher does not work out, you have a great career as a tour guide awaiting you,” I assure him, eliciting a big smile and twinkly eyes. “Welcome anytime!” he calls out. “If you ever come back, just ask for Zaid. I will be waiting.” Our train ride back to the Ardennes for the Hoge Ardennenroute’s final section is livened up by a squealing toddler and an entire Scout group. With ringing ears, we digest the journey so far – along with a pain au chocolat – on a tea room’s terrace in Bouillon. But the action-packed morning is far from over. A delivery truck’s side mirror taps a first umbrella, causing the entire row to topple over like dominoes, targeting the table of an elderly couple that manages to jump up just in time. Luckily, no cappuccinos or croissants are harmed in the process. As we set off on our steep climb out of the valley, the tourists relaxing on the river in hot-pink pedal boats adorned with giant swan heads soon drop out of sight. Accompanied by the local youth’s speakers blasting Estelle’s American boy, we make our way up the grand watchtower for one last view over the old town. At last, we reconnect with the woods’ solitude. A whole other range of sounds takes over: a finch singing cheerfully, bees buzzing past and a soft breeze rustling the maple leaves that shield us from the sun, while the river Semois leads us to an idyllic lunch spot. The trail then hits us with a second long climb before guiding us through dense vegetation. By the time we reach the quiet town of Vivy, the muggy weather has made our water supplies dwindle. A local lady kindly fills up our bottles, while a jeep flies by with screeching tires, Belgian flags waving from the sides and young lads dangling out the windows. The whole country is getting ready for the kick-off against Italy tonight and we could not feel further removed from the Euro madness. Following the match from the forest through texts and emojis from friends and family, we give up after the first half. Disgruntled boars trot past our tents all night, clearly as upset by Belgium’s loss as we are. A less romantic version of nature A blueberry bush graciously supplements our breakfast in the morning, while the fresh paw prints in the mud allow us to speculate who else passed by last night: a deer, some squirrels, a fox? Through dewy fields we reach the town of Naomé, where a bench by the church calls our names. As we let our socks dry, we take another peek at the weather forecast and try to estimate how far we can still make it before the elements catch up to us. “Do you ever wonder if we just romanticize nature when we’re in the city?” I ask Katrien, while staring down at my legs that have been transformed into battlefields by the nettles, ticks and horseflies, all eager to leave their mark. “Nature sure isn’t always kind.” A narrow trail winds up and down along the Our until the Lesse takes us further towards Daverdisse. On a comfortable looking rock, we sit in silence and try to catch our breath. But nature grants us little respite: mosquito swarms have started their evening shift, giving us just the push we need to rush further up the hill. Thrilled that the storm seems to have blown over for the night, however, we count our blessings. When we finally sit down for dinner in the beautiful forest we call home for the night, a hare pops his head around a rock. The moment his eyes meet mine, he shoots off into the bushes. In the morning, a little mouse greets me as I open my tent door to find clear blue skies and pleasantly warm sunrays piercing through the foliage. We pack up and sprint towards the finish line, stopping only at an old mining site to marvel at how resilient nature truly is. The multitude of mountain bikers and fishermen indicate that we are nearing Mirwart and with only five kilometres left to go, the predicted showers finally erupt. After starting our adventure on the Hoge Ardennenroute in the snow in April and bathing in the sun in June, it feels only fitting to finish during a summer rainstorm in July. Having walked 278 kilometres through some of the most beautiful parts of the country, I can safely say that although nature may not always be kind, I would let it bite me all over again in a heartbeat. Practical info

Other blogs on the Hoge Ardennenroute

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed