|

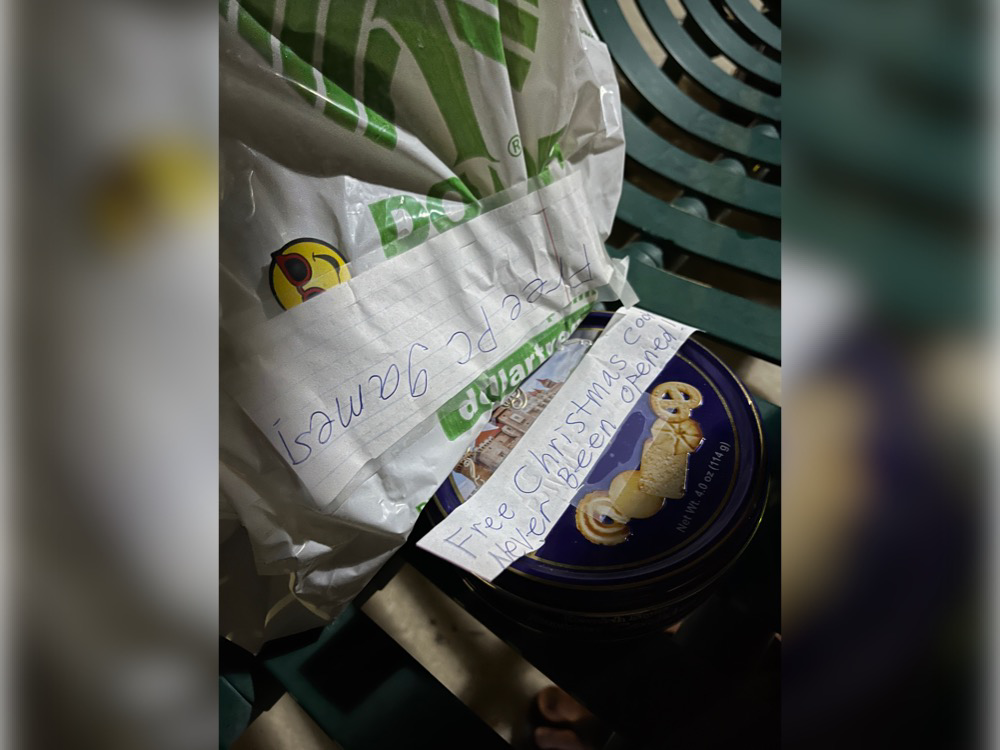

Applause. That’s how every hiker is welcomed to Kennedy Meadows by their peers. We got our round of it this afternoon, when we officially completed the PCT’s Southern California section. 702 miles — or 1.130 kilometres — of desert hiking, which is pretty rad. Or in the catchphrase of our Latino hitch into Tehachapi: “That’s wassup”. For the past two months, we walked through barren hills and green forests. We admired the yucca plants, Joshua trees and colourful flowers, while becoming skilled at avoiding poison oak and poodle dog bush. We hiked through snow and fog, were sandblasted by the wind and melted in the heat. We day hiked, night hiked and siesta-ed during the hottest hours. In short: the desert was diverse, challenging and often surprising. We are fortunate to have made it here without any real injuries, although the hiker hobble most certainly is real. This well-known hiker phenomenon turns my body into that of a 90-year-old for the first two minutes after I get up, no matter how briefly I sat down. The desert also reminded us that growth is often painful and messy. While we were hoping to hike bigger days by now, our average daily pace has plateaued at 27 kilometres. Not getting frustrated when we see other hikers fly by is a lesson we are still learning. Our town days in the desert were almost as colourful as the time we spent on trail. From being offered rides and a bottle of wine to accepting cold drinks, breakfast and coffee from numerous trail angels. We slept in makeshift bunk beds next to a creepy, old doll in Big Bear and stayed with a gun loving Scientologist in Wrightwood. In Tehachapi, we fell victim to the elderly widow’s jokes while hitching a ride and were subjected to her impressive vocal range, as she burst into song before letting us out of her car. My new favourite town hobby is rummaging through hiker boxes on the hunt for free food and gear. I even ate a box of cookies someone had left behind on a bench with a note saying they had never been opened, because free calories. Tomorrow, we head out into the Sierra Nevada with a new pair of shoes, ready to take on different challenges and be rewarded with stunning views. But before we do, here are some random facts about our desert hike:

6 Comments

13%. That’s how much of the PCT we already completed: 342 miles or 550 kilometres. Tomorrow, we will be halfway done with the desert, which is hard to wrap our heads around. As I was loitering outside Big Bear’s post office last week, a German couple asked me how it has been so far. “It has been everything,” was the most honest answer I could come up with. Hot N ColdI figured, why try to find the right words to describe the desert, when Katy Perry has already summed it up so accurately? ’Cause you're hot then you're cold You're yes then you're no You're in then you're out You're up then you're down You're wrong when it's right It's black and it's white We fight, we break up We kiss, we make up (You) You don't really want to stay, no (You) But you don't really want to go You're hot then you're cold You're yes then you're no You're in then you're out You're up then you're down From blistering heat to freezing cold, the desert has most definitely been a lot of yes and no. It was In-N-Out (the burger chain, that is), and up and down (looking at you, San Jacinto). We were wrong when we thought we could send our rain gear home and right when buying those microspikes. It was black from all the burnt trees and white from the snow. We fought tens of blowdowns, briefly broke up with the trail when hitching a ride into Julian for a doctor’s visit, but kissed and made up when we were awe-struck by the Whitewater Preserve. We didn’t really want to stay another day in Idyllwild to wait out the storm, but we also didn’t really want to go. It definitely was hot and cold, yes and no, in and out, up and down. Mental hoopsWe are doing great physically. Apart from feeling tired most days and a few blisters here and there, our bodies seem to be handling the daily exercise well and have already gotten stronger. Instead, it is the mental hoops the trail is making us jump through that have been the bigger challenge so far. Constantly being on the move felt draining at first and by trying to keep up with other hikers, we became very focused on our pace. We pushed harder than we should have until we felt burnt out and were questioning why we were even out here. I was frustrated that my legs could “only” carry me 15 miles a day and felt pressed to get up early every morning to rush to the next milestone. There’s also quite a bit of keeping up appearances on trail. Many hikers claim to be “just cruising,” “feeling absolutely fantastic” and “loving every minute,” as they “crunch those miles.” Listening to these narratives made us feel inadequate at times for not always having a blast. Don’t get me wrong, there are definitely amazing moments, but it is also a lot of hard work and discomfort. For the first two weeks, we were just going through the motions of thru-hiking: packing up, making miles, completing camp chores and sleeping. We were checking the same boxes over and over again without having the energy to enjoy the beauty that surrounded us. Eventually, we realised we were carrying a lot of social pressure with us on trail, while one of the main reasons for us to be here was to get away from exactly that. So one morning, when everyone had already left by 6:30 to sprint up the mountain, we decided to slow down instead. We watched the hummingbirds drink, the gopher dig and the rattle snakes sunbathe. And it was glorious. HYOH (hike your own hike) might be a popular hashtag, but the concept probably isn’t practised enough yet on trail. So from now on, this hike is about me. It’s about us. As much as I would love to reach Canada at the end of all of this, arriving anywhere is no longer the main goal. We’ll get to wherever we need to be, while taking it all in and enjoying our time with the people around us. Trail magic and communityEven though we don’t have our trail family yet, we do have the pleasure of hanging out with some pretty cool people whenever we run into them.

Take Michael, who passionately told us all about the moose he photographs back in Colorado, or Jonah, Kate and Xander, who taught us the important skill of eating Oreos handsfree. And then there’s Graham, who convincingly argued that the birds are just singing about cheese burgers all the time, or Becca and Andrew, who stepped into horseshit right in front of our eyes one day and who we ended up boating with on Big Bear Lake the next. What also helps us keep going, are the many encouragements and acts of kindness from strangers. It’s trail angels such as Francesca, who helped me plan a surprise birthday party and went out of her way to help us get the necessary medication when the nearest pharmacy was an hour away from us. It’s the lady who brought us donuts in the parking lot and people we never even met, who left us grapefruits under the underpass or a cold soda after a harrowing 30 kilometre descent. It’s people like Mario, who spontaneously offered us a ride back to the trail, while we were just having ice cream outside a gas station. It is all the passersby that strike up a conversation and encourage us. While Canada is still too far to even think about and thru-hiking will always be a lot of hot and cold, we are finding more and more joy in this strange hikertrash lifestyle every day. “You’re not going alone, are you?” In every conversation I have had about my upcoming PCT thru-hike, the question has popped up. Initial enthusiasm quickly fades into concern, until people learn that I am starting off with my boyfriend. “Oh, that’s fine then, because all alone …” For the longest time, I assumed everyone setting off on an epic adventure, such as hiking all the way from Mexico to Canada, received the same level of concern. Turns out that’s not the case. I recently asked my partner whether he gets the same reactions: “People do ask me if I am going alone, but their main worry is that I will be lonely, not that it would be unsafe.” The funny thing is that not everyone seems to mean “it’s good that you’re going with someone,” when they voice their relief. What they are really saying – perhaps even subconsciously – is that it is good that I am going with a guy. When I set off on hiking trips with female friends in the past, not all sceptics were reassured. Conclusion: while going with another woman is good, being accompanied by a man is still considered safer. Gender-based concernThe disapproval of me adventuring solo is often phrased very subtly. Sometimes as direct criticism, but usually it takes the form of well-intentioned concern. And concern is not a bad thing. It is a sign of love and care that should be taken into consideration. But it becomes problematic when it is tied solely to my gender instead of to my skills and experience level. While there are still very real risks involved with being a woman in most places in the world, the dangers I am most likely to face in the wilderness will not discriminate. A bear does not care about my gender. A river will not pull me under more. A tree is not more likely to fall on me. And I am not more prone to slipping and falling, getting lost and dehydrated, or being struck by lightning than any man on trail. And yet, the narrative I hear time and time again implies that I am somehow more fragile and less capable of making it on my own in the backcountry. While male peers are encouraged and praised for their bravery and strength, I am regularly told – directly and indirectly – that I am simply “lucky” nothing has gone wrong so far. The message is clear: it is not my careful evaluation of situations and sound judgement that guide me through adventures safely, but sheer luck. It is only a matter of time before my “irresponsible behaviour” turns me into the next headline, if I am to believe the critics. "Concern becomes problematic when it is tied to your gender and not to your individual skills and experience level." Rethinking the narrativeThe human brain is wired to believe the information it is fed systematically. Narratives like these leave women – like myself – feeling insecure and hesitant to take on challenges. They place mental barriers in the way of women wanting to explore the outdoors and instill misplaced fears they will actively need to overcome to pursue their goals.

On this International Women’s Day, let’s rethink the narrative. It is ironic that we still teach women to ignore and downplay inappropriate male behaviours that could actually harm them, yet discourage them from going after empowering experiences that will better equip them to stand up for themselves in the face of real threats. So when I set off soon, show me that you care, but do not ask questions you would not ask if I were a man. Because quite frankly, I am tired. Tired of being deemed lucky instead of capable. Tired of hearing the world is too dangerous for me and that it would be foolish to think otherwise. Tired of having to prove my worth, while I know the strength that resides within. Care to break a leg next time you’re out hiking with me? Develop mild hypothermia or suffer from heat stroke? You’d be in good hands. After four days of lectures, drills and simulations, I am officially Wilderness Advanced First Aid certified! In December, Stefaan and I signed up for a four-day Wilderness Advanced First Aid (WAFA) course taught by Wilderness Medical Associates International and hosted by Outward Bound Belgium at the Chateau Varoy in Anhée. From 8:30am until 6pm, we broke limbs, burnt ourselves, fell out of trees, got hit by lightning, cut our arms, went unresponsive, developed severe hypothermia, had allergic reactions, experienced volume shock, hit our heads, choked, suffered from urinary tract infections, had strokes and heart attacks, … You name it, we had it! Four intensive days of lectures and drills taught us how to assess emergency situations and provide medical assistance in the field. We also learnt to determine when an emergency evacuation is necessary and how to get a patient out as safely as possible, while also keeping ourselves and others out of harm’s way. Signing up for a WAFA course had been on my mind for years, but it turns out that I am incredibly skilled at making up excuses. Medical conditions have made me squeamish for as long as I can remember, sometimes even making me faint. But with huge hiking plans on the horizon, it only felt right to do the responsible thing and finally take the course … … which leads me to the big announcement. Two years after the pandemic cancelled my plans to thru-hike the Pacific Crest Trail, Stefaan and I will finally be setting off from Campo this April! If all goes well, we should arrive at the Canadian border sometime in September. I sincerely hope none of my future blogs will include any of the techniques we practised during the course. But if disaster does strike, I now feel confident that I will handle the situation in the best way possible. While first aid courses aren’t cheap, that peace of mind is priceless to me. Photos by Diederd Esseldeurs, Stefaan Van wal and myself

At 30 years old, I am yet to discover what going with the flow means exactly. If I am not busy executing a plan, you will likely find me in the middle of hatching one. When I decided I would hike 2,650 miles from Mexico to Canada, I knew it would be impossible to be in control the entire time, however. So I prepared mentally.

Fire closures? No problem, we’ll find an alternative route. Current too strong to cross? No big deal, we’ll just turn around. Injured? When our bodies heal, we’ll continue. Whatever the trail would throw my way, I was ready to take it on and adjust my plans accordingly. Oh, how wonderfully flexible I thought I had become. Just when I believed I had mastered the skill of expecting the unexpected, my newfound stoicism was put to the test. Words like travel ban, coronavirus, self-isolation and lockdown quickly made their way into every conversation. In the blink of an eye, an ever-growing list of temporary measures was put in place, with the word 'temporary’ still up for definition. While researching the Pacific Crest Trail, I had read thru-hikers’ testimonies of post-trail depression, yet none had warned me of pre-trail despair. The kind that results from quitting your job, uprooting your life, and preparing mentally and physically, only to wake up to a world you no longer recognise. In the face of adversity, my coping mechanisms of choice tend to be lists and scenarios. Only this time, the nature of the crisis did not allow me to rely on my old ways. As I found myself stuck in limbo, I scrolled through my pre-trail mental prep notes:

While these lessons are now brought to me by COVID-19 instead of by the trail, they ultimately remain the same. And so, I try to apply them to my new circumstances, as it is looking less and less likely that my feet will touch the trail anytime soon. Other concerns will have to take priority, while we collectively overcome unprecedented hurdles and hope that better times lie ahead. So for now, I wash my hands, set my mini goals and embrace the suck. I first learnt about the Pacific Crest Trail (PCT) by the deserted ticket booth at the back entrance to world heritage site Petra. Living in Amman at the time, I was walking a section of the Jordan Trail when a bearded hiker asked: “Is this where we show our Jordan Pass?”

Mitch had travelled from Australia to thru-hike the Jordan Trail as a warm-up for the PCT. Having spent the last couple of nights by himself in the desert, he seemed happy to have found some company. When he told me about his aspiration to hike all the way through California, Oregon and Washington for five months, I thought he was out of his mind. My five-day stint from Dana to Petra had seemed rather heroic to me at the time; five months, on the other hand, unfathomable. And yet somehow here I was, standing in line outside the U.S. embassy in London on a cold, but sunny morning a year and a half later. After handing over my documents, I queued for the final hurdle: the visa interview. The consular officer smiled sympathetically at the young couple in front of me, struggling to contain their toddler’s inexhaustible energy reserves. When it was my turn to approach the window, her smile quickly turned into a frown.

Her blank stare made me wonder whether I was conveying my desire to walk all the way from Mexico to Canada adequately enough. “We will fly to San Diego, make our way to Campo and then walk for 2,650 miles until we reach the Canadian border,” I rushed to clarify, without appearing to alleviate any confusion. Fortunately, the wish to travel the length of the United States on foot is insane enough for it to have to be true. So after a multitude of questions, her verdict was reached: “Your visa application has been approved and will take three to five working days to process.” And just like that, my attempt at thru-hiking the Pacific Crest Trail became a reality. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed